First-of-its-kind study highlights impact on San Diego economy, including $11B generated and more than 100K employed

Of note, data collected is pre-COVID from 2019.

In order to better understand the impact on our communities, EDC and the City of San Diego have released the first comprehensive study analyzing the intersection between San Diego’s creative industries and the local economy.

Together with the City’s Commission for Arts and Culture and the Economic Development Department, EDC authored the 2020 Creative Economy Study to examine the economic impact creative industries and their workers have on the region.

“San Diego’s creative industries have an important ripple effect in the broader economy. Every job in the creative industry supports another 1.1 jobs,” said Christina Bibler, Director of the City’s Economic Development Department. “This means that creative industries are a powerful component in the region, with many industries employing creative workers.”

The creative economy is defined as a sector made up of non-profit and for-profit businesses and individuals who produce cultural, artistic and design goods or services and intellectual property. In San Diego, the creative economy employs more than 107,000 people at nearly 7,400 creative firms and organizations and generates more than $11 billion annually.

“To grow San Diego’s creative economy, we first need to understand it. This report is the starting point to understanding the space and trends over time,” said Jonathon Glus, Executive Director of the Commission for Arts and Culture. “Investing in creative industries can help advance San Diego as a creative city and it’s the ideal platform for cross-sector collaboration and innovation.”

The study measured the size of the creative economy and identified characteristics unique to San Diego that could provide future economic growth potential. The study spanned 71 industries and 77 unique occupations.

Study findings include:

- 59% of the creative economy in San Diego is for-profit, 34% nonprofit and others (including government employers and independent contractors).

- The majority of creative firms and organizations are small, with 19 or fewer employees.

- 41% of creative industry employers hire a large number of contractors.

- The median annual income for creative occupations is $75,000.

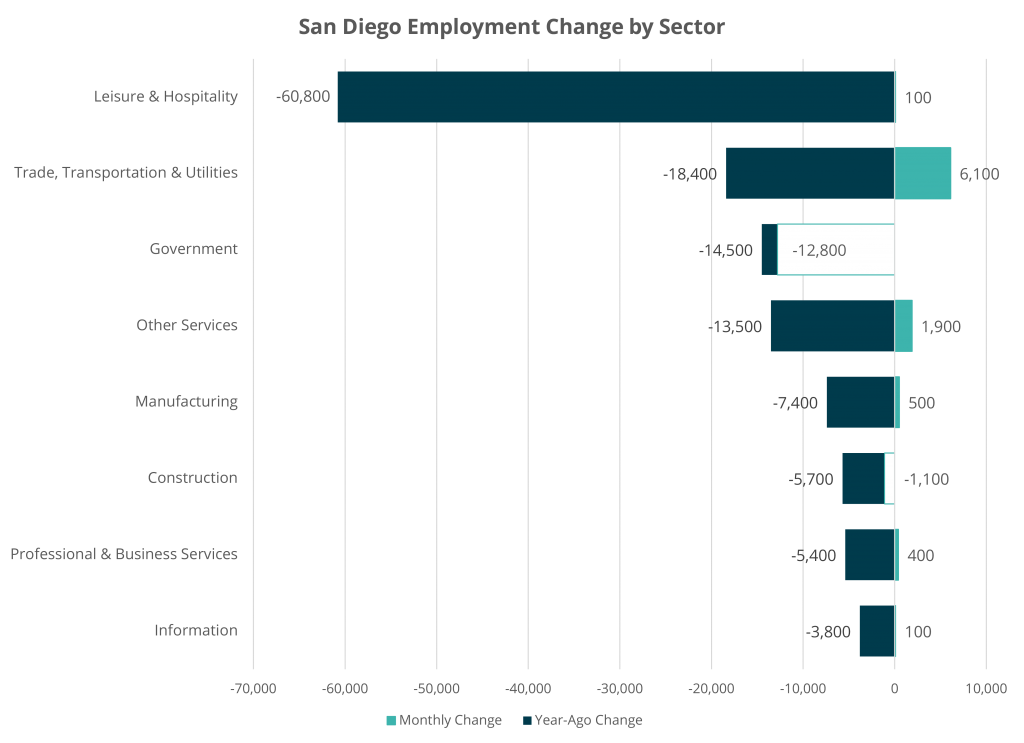

“With a 23% decline in jobs, the arts have been hit even harder by the pandemic than most sectors of our economy,” said Mark Cafferty, president and CEO, San Diego Regional EDC. “As San Diego recovers, it is imperative we continue to work with our arts and cultural leaders to create a more diverse and resilient arts industry to weather future economic downturns—for the sake of the vibrancy of our communities and our culture.”

Completed in May 2020, the study utilizes 2019 information. The data was collected pre-COVID-19 and prior to the implementation of Assembly Bill 5 Worker status: Employee and Independent Contractors (AB 5).

As of August 2020, the economic impact of job loss in San Diego’s creative industries due to COVID-19 is estimated to be a decline of $2.1 billion.

You also might like:

- San Diego’s Economic Pulse: October 2020

- San Diego’s economic recovery must be inclusive.

- Research and Data

For more COVID-19 recovery resources and information, please visit our COVID-19 resource page.